Chronic Training Load & Why It Matters

If you have used WKO+ you’ve seen the Performance Manager Chart (PMC) that shows your Chronic Training Load (CTL). Most people I talk to look at the chart and think “Gee look at the pretty lines and colors.” But when used correctly, the CTL line on that chart gives you an idea of what you’ve done and what you can do. It needs to be looked at along with the other pretty lines in your PMC, but for now I’ll give the down and dirty on CTL.

When you train you stress the body. You adapt and hopefully over repeated weeks, months and years of training you get faster AND you can handle higher workloads. Today’s hard 5×5 minutes of threshold on the bike that makes you hit the couch for a two hour nap, becomes tomorrow’s 8×5 minutes of threshold that leaves you tired but able to grocery shop right after. Today’s training becomes tomorrow’s chronic training load. Different training has different stresses and impacts your CTL differently. Your CTL is measured in Training Stress Score / Day. Think of this as how much stress you give yourself based upon what you do. A hard interval session where you knock out 4k of intervals and run 9k total will give you more TSS then a 10k easy run. A 2.5 hour ride where you flog yourself for 75 minutes of threshold will yield more stress then a 2.5 hour coffee cruise. If easy coffee cruises added a ton of stress, instead of social rides to have a coffee we’d have climbing rides to socialize.

Since TSS makes up part of your CTL the more you do in any one day the higher CTL goes. It also rewards consistency. Remember CTL = Training Stress Score / Day. It’s the cumulative training you’ve averaged per day for how ever long you want to look at it in your PMC. (This is why it’s a good idea to run more than one PMC.) If your PMC is set for 52 weeks, it’s going to take more to increase or more time off to decrease your CTL compared to a PMC that is set at 28 days. The more consistent you are in training daily, the more you can influence up or down your CTL. Big training days typically add to your TSS/D, days off of training subtract from it.

To give you an example of how this works let’s choose 165.5 TSS/D, this means you’ve averaged 165.5 TSS per day every day you’ve trained for however long your PMC is set for. If you only train 50 TSS today it will drop a little. If you train 257.8 TSS it will rise a little. Generally you want this to rise over time and get as high as possible. It’s this long term rise in what you have done that allows you to do more. It;s this long term rise that is the result of training. A U23 rider isn’t going to have the same sort of CTL that a veteran cyclist who has ridden 10 Grand Tours over the last 4 years is going to have. But depending upon how long you set your PMC for and what each of these riders has been doing recently the U23 rider might have a higher ATL (Acute Training Load) then the veteran tour rider.

You have to look at CTL in both the short and long term. If you only look at the long term CTL you might miss the day in day out picture of what you have been doing very recently. Huge ramp ups over short periods of time can leave you tired and performing poorly if not managed proprely. On the other hand, if you only look at your PMC over the short duration, you won’t see what you’ve done long term and might miss clues to what you could be doing or should be doing.

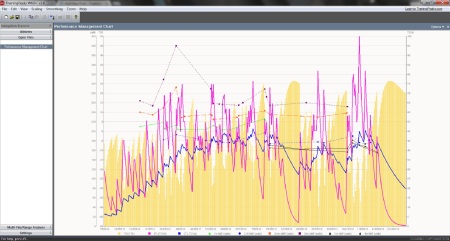

Below I’ve inserted a PMC of one of my athletes from last season. I’ll talk about some of the things that influenced the CTL aka blue line.

To look at the season as a whole you’ll start from the left and look right. This will give you an idea of where they started and where they ended up. This was a new to me athlete and I had no historical data from them from previous years. The first four and a half months were spent training. You see the steady saw tooth progression of the CTL line. This represents the pattern that the first four and a half months fell into. A few bigger/harder days and few easy days. The intervals were short, hard and often. There wasn’t a lot of threshold riding, there was a lot of supra threshold riding. This continued right into the first weeks of racing where multiple races where raced. You’ll notice the big dip in the blue line. This is where significantly less training per day was being done. Once we got through this period we started a push towards the first major race of the season. You’ll notice the blue line starts trending up. If you were to look at a short time frame PMC you’d see a significant spike in the acute training load of this athlete. The duration’s and intervals changed to reflect the specificity of the events that were being focused on for the season. This athlete had to do more to maintain and increase their fitness as they acquired more fitness. The next major dip in the blue line represents a mid season break from training. This was a 7-10 day break from training to help manage fatigue loads. The build up that followed was much like the previous ramp up. The ATL was very steep, representing lots of work in a short period of time, but not short workouts. The next major dip was work related that required a couple of weeks of almost around the clock work. This curtailed training and you can see that as the blue line drops. This was followed by two more ramp ups with some drops due to work related stuff. Each of these build ups had an ATL that was much steeper then the long term CTL you are seeing here. This TSS was achieve with some very long rides and runs acquiring large amounts of TSS in a very few workouts and little TSS in the rest of their workouts. Frequency also dropped a little compared to early in the season in some sports. The final ramp up saw this athlete achieve some of their highest ATL numbers of the year and near season high CTL numbers. This huge increase in ATL led into tapering which allowed both short and long term CTL to drop.

Hopefully you can now understand that ATL and CTL influence each other and how both have to be managed for a successful season. By looking at the CTL, short and long term, and the athletes race schedule, you can learn to manipulate training loads to be at optimal fitness for the races that matter. This allows you to do the training that matters so you can get results that matter at the races that matter.

January 9, 2013 at 1:00 pm

I wouldn’t overly obsess about TSS or CTL (mostly with veterans). This can lead to who is the best exerciser. Rather specificity trumps all. If I have someone _just_ do 3 days per week of VO2/Z5 type stuff and nothing else, they wont have a huge amount of CTL but they will eventually adapt to that work and give themselves a much higher aerobic ceiling to then work with for raising threshold to. One instance where I do think the statement “get your CTL as high as possible” is valid is in preparing for an IM. Given the vast amount of load the athlete will go through on race day it’s specific to the process to load them up with a ton of stress leading to it.

May 23, 2013 at 8:37 am

[…] less – but still consistent – training, which this was not. Consistency is critical; for a technical look at why, this article by Brian Stover is pretty good at explaining the concept o…. While I could attempt to follow the trend in current society to “put a positive […]